Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Personal Reflection on Literature, Freedom, and Exile

Literature, Censorship, and Leaving Home: Reflections on 'Reading Lolita in Tehran'

Whenever someone asks me why I moved to London, I give them obvious answers, but the truth is much deeper. Actually, it’s quite a story—one that, in some chapters, mirrors the experience of many immigrant Iranians. Reading Lolita in Tehran could easily be a chapter in the book of my reasons for leaving my country!

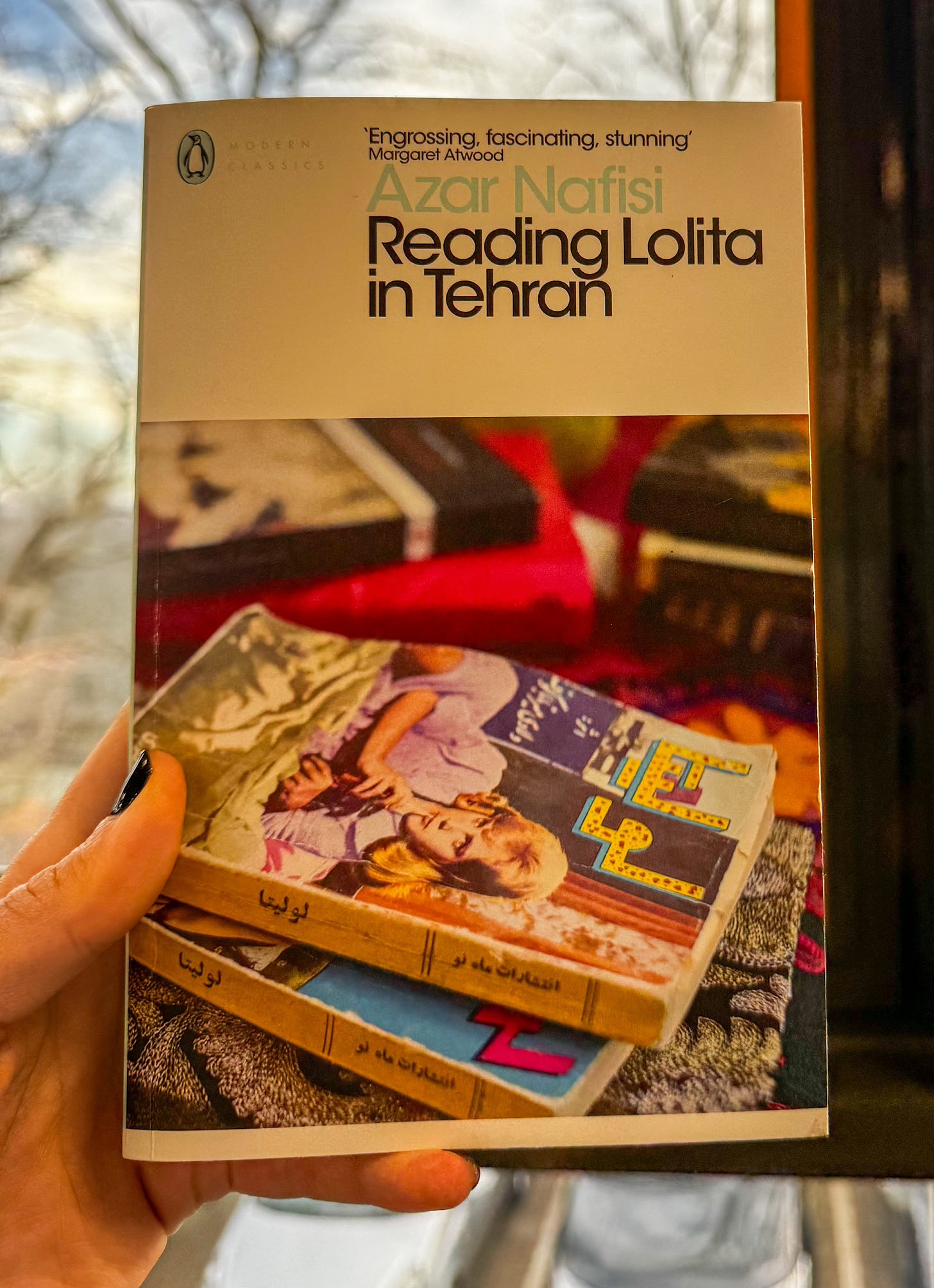

Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003) is a memoir by Azar Nafisi, blending personal experience with literary analysis to explore life in post-revolutionary Iran.

About Reading Lolita in Tehran

I was born in 1990, two years after the Iran-Iraq war. Reading Nafisi’s memories about that time reminded me of my own childhood—the fears, the blurry hopes about my life as a girl in my country.

The book follows Nafisi’s experiences as a literature professor in Tehran, where she secretly gathered a small group of female students to read and discuss Western classics: Lolita, The Great Gatsby, Pride and Prejudice, Henry James' works, and Madame Bovary.

She believed literature could teach people how to live and cope with challenges:

“...how these great works of imagination could help us in our present trapped situation as women. We were not looking for blueprints, for an easy solution, but we did hope to find a link between the open spaces the novels provided and the closed ones we were confined to. I remember reading to my girls Nabokov’s claim that ‘readers were born free and ought to remain free.’”

What made this book special to me was not just its powerful narrative about being a woman in Iran, but also the way she, as a literature professor, taught us how to interpret stories and learn from them—just like she did with A Thousand and One Nights:

“Before Scheherazade enters the scene, the women in the story are divided into those who betray and then are killed (the queen) and those who are killed before they have a chance to betray (the virgins)... Scheherazade breaks the cycle of violence by choosing to embrace different terms of engagement. She fashions her universe not through physical force, as does the king, but through imagination and reflection. This gives her the courage to risk her life and sets her apart from the other characters in the tale.”

Reading this book felt like being in a literature class. See how beautifully she explains how we should read novels:

“A novel is not an allegory, I said as the period was about to come to an end. It is the sensual experience of another world. If you don’t enter that world, hold your breath with the characters, and become involved in their destiny, you won’t be able to empathize, and empathy is at the heart of the novel. This is how you read a novel: you inhale the experience. So start breathing. I just want you to remember this.”

Another reason I loved this book was that, for the first time in my life, I was reading a story about my country without censorship. It was real. I could relate to it, I could enjoy it. It made me angry, sad, sometimes even made me cry—but it was real!

I experienced the same things she described. It felt good to feel heard! She taught at the same university where I studied for my master’s—Allameh Tabatabai. Years after her, I experienced the same discrimination. Before entering, there was a separate gate for women. An angry woman, dressed in all black, in her Chador, was always there, checking our clothes, making sure our makeup wasn’t too much, inspecting our nails. Once, I had nail polish on, and she forced me to remove it before I could enter the university.

By our time, they had even separated classes for boys and girls. After class, we gathered in the university courtyard to talk. As their restrictions grew, we became more courageous, more rebellious. This is how the author describes our university:

“Yet that green gate was closed to her, and to all my girls. Next to the gate there was a small opening with a curtain hanging from it... Through this opening, all the female students went into a small, dark room to be inspected. Yassi would describe later... ‘I would first be checked to see if I had the right clothes: the color of my coat, the length of my uniform, the thickness of my scarf, the form of my shoes, the objects in my bag, the visible traces of even the mildest makeup, the size of my rings and their level of attractiveness... all would be checked before I could enter the campus.’”

Their Thursday classes became a ritual—a space where they discussed their lives as women in society, in their families, and among themselves. Through these discussions, Azar and her students reflected on oppression, resistance, and personal freedom, drawing parallels between fiction and their own lives under Iran’s strict theocratic regime.

One important thing to mention: Just because we lived in a restricted Islamic country doesn’t mean we accepted our fate and did nothing. I was reading this book during my lunch break at work when my colleagues asked me about it. One of them asked me the same question my university supervisor in London once did: Could you drive in Iran as a woman? I laughed—of course, I drove there! Of course, I worked as a senior manager! Living under restrictions doesn’t mean we stopped living. We had our secret parties, we made our own homemade drinks, we wore whatever we wanted at private gatherings. The problem was, and still is, that we were always being watched. If a woman doesn’t cover her hair while driving, they fine her. If they catch you drinking alcohol, they lash you. But none of this stopped us from dreaming and living the lives we wanted!

Immigration

After about eighteen years in Tehran, Azar decided to leave for the U.S. She left in 1997, when I was seven. When I left Tehran in 2022, I had the same, and even more, reasons to leave.

To keep it short—like the opening of her epilogue—I left Tehran for the same green light that Gatsby once believed in.

Like her, I always tried to live in freedom. I left my hometown in my 18th to move to Tehran—a city with more opportunities, more freedom. And yet, it wasn’t enough.

I feel all my life has been a series of departures.

When I completed my second master’s in London, some of my classmates chose to return to their home countries. They felt staying here wasn’t worth it. And while I do like it here, I was heartbroken to realise that, unlike them, I didn’t have a choice. At least they had a home to return to.

My yearning was tied to the certainty that home was mine for the having, that I could go back anytime I wished. It was not until I had reached home that I realized the true meaning of exile.

There’s a song by the legendary Iranian singer Fereydoun Farrokhzad called ‘Melancholy Eastern (Sharghie Ghamgin).’ Whenever we find moments of happiness here but hear about another tragedy in Iran, we call each other ‘Melancholy Eastern.’ As Nafisi puts it:

Going away isn’t going to help as much as you think. The memory stays with you, and the stain. It’s not something you slough off once you leave.

When I returned to Iran after two years to see my family, I realised just how much I had changed. I remembered who I was there, and in some ways, I missed that version of myself. But I believe life is about moving forward, about finding meaning. No matter where we’re born, we all have the right to seek peace and joy. Home isn’t just a place—it’s the people we love, the culture we carry, and the memories we cherish.

Like you’ll not only miss the people you love, but you’ll miss the person you are now at this time and this place, because you’ll never be this way ever again.

About the Author

Azar Nafisi is an Iranian-American author, professor, and literary scholar best known for her memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003). Born in 1948 in Tehran, she studied in the United States before returning to Iran, where she taught literature during the Iranian Revolution. Her work often explores themes of freedom, censorship, and the transformative power of literature, particularly in oppressive societies. Nafisi later emigrated to the U.S., where she has continued to write and advocate for intellectual freedom and women’s rights. Her other notable books include Things I’ve Been Silent About and The Republic of Imagination.

At the End

I felt this book with my whole heart. And if someone wants to understand why we choose to leave a beautiful country, our families, our successes, and our happiest moments with loved ones, this book offers a powerful explanation!

Thanks for reading☺️ If you liked this review, press ❤️ and share it with your friends!

Very intriguing review, and I’m fascinated reading how you relate your own experiences. Thank you for sharing...I’ve got a new author to look into!✌️

Really interesting piece, and adding this one to be TBR list - thank you! 😊